This article is an analysis of the newly passed ‘Regulation on Privacy and Electronic Communications’ passed by the European Union. A huge part of our daily life now revolves around the usage of websites and communication mediums like Facebook, WhatsApp, Skype, etc. The suddenness with which these services have become popular left law-making authorities with…

Category: Regulation

Fake News and Its Follies

Fake news may seem to be very innocuous and in fact might not seem to cause much harm to anyone or have any real-world consequences. Fake news is a phenomenon where a few individuals, sites and online portals create or/and share pieces of information either completely false or cherry-picked from real incidents with the intention…

RELIANCE JIO: REGULATORY AND PRIVACY IMPLICATIONS

Ed. Note.: This post, by Sayan Bhattacharya, is a part of the NALSAR Tech Law Forum Editorial Test 2016. In the world of technology dominated by a power struggle in terms of presence and absence in data circles, Reliance Jio has probably made the biggest tech news of the year with its revolutionary schemes. By…

LEGAL ISSUES SURROUNDING SEARCH ENGINE LIABILITY

Ed. Note.: This post, by Sayan Bhattacharya, is a part of the NALSAR Tech Law Forum Editorial Test 2016. Search engines which are quintessential to our internet experience are mechanisms of indexing and crawling through data to provide us with a list of links which are most relevant to both our present and past searches….

The Right to Be Forgotten – An Explanation

Ed. Note.: This post, by Ashwin Murthy, is a part of the NALSAR Tech Law Forum Editorial Test 2016. The right to be forgotten is the right of an individual to request search engines to take down certain results relating to the individual, such as links to personal information if that information is inadequate, irrelevant…

Privacy – A right to GO?

Ed. Note.: This post, by Ashwin Murthy, is a part of the NALSAR Tech Law Forum Editorial Test 2016. For centuries rights have slowly come into existence and prominence, from the right to property to the right to vote and the right against exploitation. In the increasingly digital world of interconnection, the latest right to…

REGULATIONS FOR SELF-DRIVING CARS

Ed. Note.: This post, by Vishal Rakhecha, is a part of the NALSAR Tech Law Forum Editorial Test 2016. Self-driving cars have for long been a thing of sci-fi, but now with companies like Uber, Google, Tesla, Mercedes, Audi and so many more conducting research in this field they don’t seem as unrealistic. Self- driving…

Uber – Into the New Tomorrow

[Image Source: http://flic.kr/p/jyCqcH] The rapid influx of technology has in recent times forced various firms to revamp their respective business models. The taxi industry is no exception. In this blog post, I will discuss the government’s ban on Uber cabs and the issue of its compliance with the IT Act, 2000 or the Radio Taxi Scheme,…

December, 2014: Fireworks and more!

December, 2014, has been the month when the Indian community received a multitude of shocks, one after the other and each one more powerful, on the issue of internet-related legal problems. First, we had the lamentable Uber issue, which was followed by Airtel announcing (and later withdrawing) its VoIP-data plan, which violated Net Neutrality down…

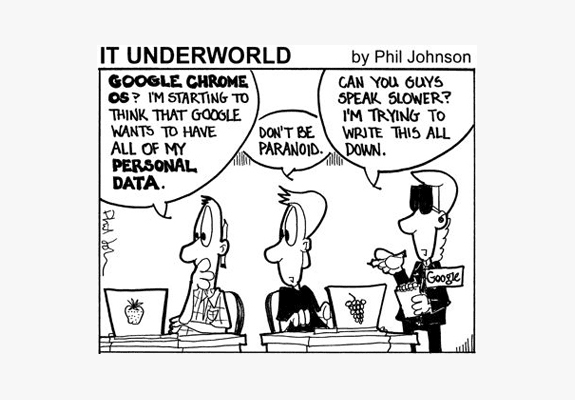

Google’s Commercial Dominance – the Problem of a ‘Free’ Economy

(Image Source: https://flic.kr/p/oHcd72) Just yesterday, the internet became abuzz with the news that the European Parliament (‘EP’) is pressurising the European Union (‘EU’) to break Google Search away from the rest of its services (such as Android, et al). We’ve covered Google’s antitrust woes with the EU on the TLF earlier. According to this Techdirt article…