[This post has been authored by Sanchit Khandelwal, a third year student of NALSAR University of Law, Hyderabad.]

The ‘digital economy’ has witnessed remarkable growth and change in the last few decades and promises to continue to do so. Deepened penetration and wider access to the internet has further helped to alter the erstwhile relationship between customers and businesses. The exponential growth of computing power has enabled the upsurge of business models based on the collection and processing of ‘information/data’ exchanged between consumers and business firms.

Tech giants have access to huge volumes of varied data, and with enhanced data processing technology, they are now able to mine and process input rapidly. They churn out valuable information in real time. With the help of data analytics, businesses are now not only able to predict behavioural patterns of customers more accurately, but can also customise products and services tailored to their customer’s needs. Through such analysis, resourceful firms are no longer dependent upon the traditional and time-consuming demand-supply chain to adjust their production.

Walmart, through data analysis, arrived at a positive co-relation between the occurrence of a hurricane and consumption of strawberry tarts. They found that the sale of strawberry tarts increased by 7 times before a hurricane. Going by the data, they started stocking up strawberry tarts and placed them at checkouts before a hurricane. Soon enough, all the tarts were sold out.

The growing influence of data over the functioning of business and the products and services offered in the market, this has resulted in a colossal divide between the business who have resources and access to data and those who don’t. The digital economy landscape replicates the societal conflict between the haves and the have not.

Data: a “bottleneck asset”

Cremer, in his report on ‘Competition for the Digital Era’ , highlighted that the competitiveness of firms has, and is likely to remain dependent upon timely access to relevant data and the ability to use that data to develop. Diker Vanberg and Ünver in their paper titled, ‘The right to data portability in the GDPR and EU competition law: odd couple or dynamic duo?’ argued that if a dominant firm possess specific data that is indispensable for other undertakings to enter a new market, and the dominant company’s refusal to transfer that data eliminates all potential competition, then, in the absence of objective justifications, Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (hereinafter referred to as TFEU) could be relied on. Article 102 of the TFEU is aimed at preventing undertaking who hold a dominant position in a market from abusing that position. The European Court of Justice (ECJ) has in several cases reiterated that if the refusal to deal would result in negative effects and reduced consumer welfare, then such conduct of an undertaking can be found to be abusive.

Analysing the impact of the data upon the competition in the digital economy, a number of experts have argued for consideration of data as an essential facility to which the ‘essential facilities doctrine’ could be applied. Here, we consider the claim of application of essential facilities doctrine to data in some markets of the Indian digital economy.

Essential Facilities Doctrine

The essential facilities doctrine found its origin in the U.S. Supreme Court case of United States vs. Terminal Railroad Association (1912). The doctrine was first applied in the EC competition law in the Sealink case. The doctrine in the Indian competition law regime was first examined in the case of Arshiya Rail Infrastructure Ltd (ARIL). The Commission noted that the ‘essential facility doctrine’ can be invoked only in following circumstances:

- existence of technical feasibility to provide access

- possibility of replicating the facility in a reasonable period of time

- distinct possibility of lack of effective competition if such access is denied

- the possibility of providing access on reasonable terms.

Although the essential facilities doctrine is regularly discussed as a tool to open up markets of the new age economy, it has not been applied recently by any competition enforcement agency. Interestingly, the Google Shopping decision of the European Commission also imposes essential facility-alike remedies but under other theories of harm and less strict conditions. The Commission ordered Google to subject its comparison-shopping service to the identical underlying process and treatment as used for other competing comparative shopping services. By framing the case as one of self-favouring by the dominant enterprise and not as one of constructive refusal to deal, the Commission chose to avoid stricter conditions of the essential facilities doctrine but providing similar remedy. From the perspective of the internal consistency of any antitrust regulatory regime, such a development is not desirable. Especially when the issue can be directly addressed within the essential facilities doctrine, by aligning its application with the underlying economic interests.

Distinct possibility of lack of competition if access to data is denied

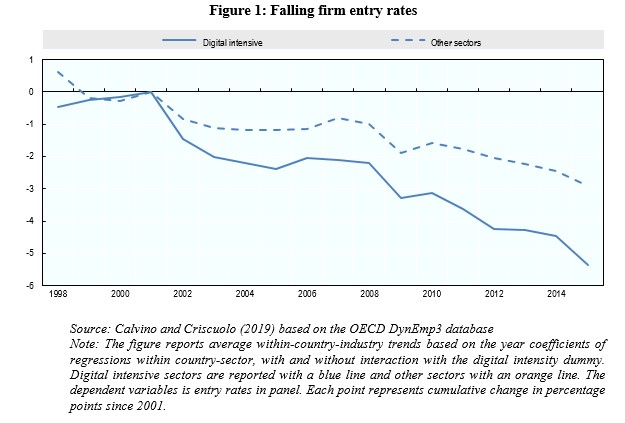

The business models in the digital economy are marred by some peculiar characteristics such as network effects, low variable costs and high fixed costs, reliance on consumer data, etc. It has been observed that the dynamic nature of the digital economy is under stress, and the market has become largely inaccessible for the new entrants. Businesses with the help of data, for accurate predictions and timely actions coupled with peculiar characteristics of the market, have been able to solidify themselves in the market. For many business models, data has become the sole consideration between the customer and the business firm. The OECD and others have found that there has been an increase in the ratio of unit price over marginal cost charged by firms. Also, evidences show that fewer firms are entering into the digital economy, thereby resulting in the enlargement of the existing firms in the digital sector.

In Commercial Solvents v. Commission, the Court of Justice argued that a dominant firm abuses its dominant position when it refuses to supply to a customer who is also a competitor in the market in order to preserve the input for itself and therefore, risks eliminating competition on the part of the customer. In Microsoft (2004), the General Court stated that it is not required for the Commission to demonstrate that all competition is eliminated as a result of refusal to license. The General Court said what matters is that the refusal ‘is liable, or is likely to, eliminate all effective competition on the market.’

Though the collection and control of even substantial amounts of data is not illegal per se, the misuse of Big Data to raise entry costs and sustain market power might amount to a violation of antitrust law that requires the intervention of competition authorities. Autorité de la Concurrence and Bundeskartellamt (2016), in their joint report, identified various ways in which firms can resort to abusive use of Big Data to foreclose the market. One way is to allow discriminatory access to data in order to provide unduly competitive gain over other market players.

An example can be drawn from the Cegedim case decided by the French Supreme Court. The firm Cegedim SA had acquired a dominant position in the market by supplying healthcare software solutions and computer services to pharmacies. On a complaint filed by ‘Euris’, a company specialising in customer relationship management software (hereinafter referred to as “CRM”), it was revealed that while Cegedim sold its CRM database to pharmacies that used its own or competing management software, it denied selling it to labs intending to use Euris’ CRM. The French Competition Authority (FCA) imposed a 5.7 million Euro fine on Cegedim on the grounds of it being ‘unjustified discriminatory behaviour’, and the same was upheld by the French Supreme Court.

Establishment of essential facilities doctrine imposes a duty to deal upon the dominant enterprise, and therefore interferes with the interest of a dominant firm. Few practitioners have voiced their concerns that while such a move surely increases short term competition, it may dwindle inducements for competitors to innovate in the long term. Such a trade-off can be presented as one between competition in the market (short-term competition) and competition for the market (competition in the long run). Competition in the market leads to innovation in sustaining technologies, whereas competition for the market leads to innovation in disruptive technologies.

Sustaining technologies presents some degree of improvement in an existing product, yet retains aspects of the product that customers value. Such technological improvement does not disturb existing markets. Disruptive technologies, on the other hand, leads to significant improvement over existing products in aspects that customers value, and gradually the new product permeates the already established markets.

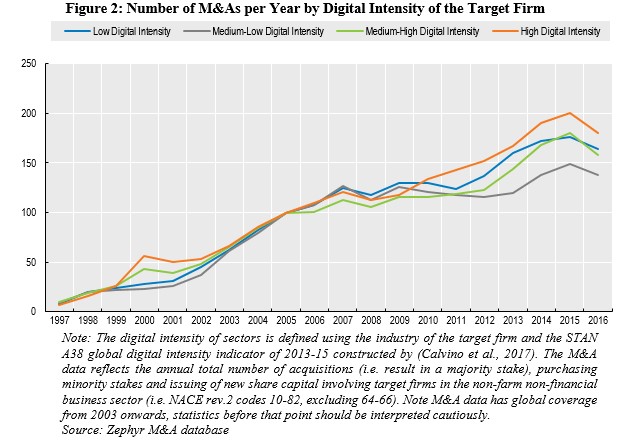

The disruptive innovations mentioned above generally come from new entrants, aiming to make a dent in the existing market. While there is no doubt that large market shares stimulate most of the new entrants to replace the incumbents through disruptive innovations, concerns arise where the market power of established players stabilise and become entrenched. This can be seen in present times. It has been observed in the last decade that whenever a company with disruptive technologies tries to break into an existing market it is acquired by dominant undertakings.

Conclusion

The prevalence of such conglomerate strategies points towards changing competition dynamics in the digital economy. Tech giants, in the last few years, have been able to break into new markets through ‘killer acquisitions’ coupled with their ability to use their data analysis to attain operational efficiency. Such developments have weakened the self-correcting nature of the market and may delay or even prevent a new wave of competition for the market from occurring.

Keeping the present market scenario of select markets of digital economy in perspective, access to data as an essential facility ensures competition in the market. A rethinking of the essential facilities doctrine along these lines prevents an unnecessary expansion of other abuses, and ensures a better alignment with sector-specific initiatives that are being developed in relation to access to data and rankings.

The essence of the doctrine is also firmly embedded in Article 39 (b) of the Indian Constitution which imposes an obligation on the State to ensure that the ownership and control of all material resources is distributed in such a way as to sub serve the common good. Therefore, the mounting competition concerns in select sectors of the digital economy can be addressed through the application of essential facility doctrine to ‘access to data.’