This is the second in my three-part series on the issue. The first and third parts are available here and here.

Tangle One

I’ll start with a side-note. In public debate, somehow, Network Neutrality ends up being represented as an absolutist concept, as “ISPs should perform no discrimination between the data travelling on their networks”. Now, as welcome an ideal as that is, the problem is that that is not practically possible, mostly because of Quality of Service (‘QoS’) concerns. This, of course, does not mean that Network Neutrality should not exist – there exist multiple proposals that reconcile these concerns with Network Neutrality, an example of the same being the application-agnostic discrimination, put forth by Barbara van Schewick.

Tangle Two

Now, for the core argument, the concerns are a bit technical. A corollary of the Schumpeterian theory is that each and every innovation that breaks a previous monopoly ends up itself being monopolised in the long run. This is what happened with the telephone, the radio, the television, and cinema. This has not technically happened with the Internet (I elaborate on the “technically” below) in some places, an exception that Network Neutrality is credited with.

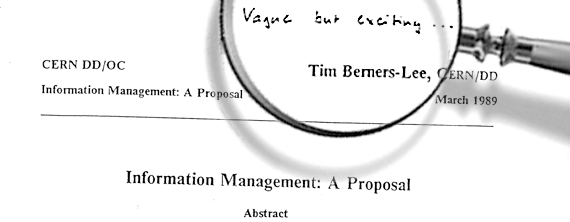

The concern this creates is, what happens, then, to the cycle of innovation? Arguably, the monopolisation of communication technologies was – crucially, only in part, and not entirely – what led to the creation of the internet as it was imagined in the 1980s and 1990s? For the sake of clarity, let’s make a differentiation here. Let’s say that the internet as it was perceived in the 1980s-1990s (mostly in the developed countries, to be honest) was the ‘original Internet’ (something which this video talks about), which prompted John Perry Barlow to make his famous Declaration of Independence of the Cyberspace (though I have learnt enough in the last few years to say that that declaration itself is problematic, and that a lack of regulation is not at all a viable proposal). And one of the core characteristics of this internet, I would argue, was ‘permission-less innovation’.

The internet that we have now is fundamentally, if not quintessentially, different from that internet – let’s call this the ‘neo-internet’. This ‘neo-internet’ is overall more convenient, of course, and is categorised by heavy regulation, surveillance and centralisation. Neo-internet cannot be characterised with ‘permission-less innovation’, at least not nearly to the same degree as the original internet. It is also characterised by increasing attempts (in frequency and power) by players in the primary market at the monopolisation of the secondary market, through either the removal of Network Neutrality principles themselves, or through their circumvention, or through a lack of extant competition and Net Neutrality regimes, so on and so forth. It is also characterised by increasing monopolisation within the secondary market itself, internet giants Google and Facebook being clear examples of the same.

And it would seem that the markets – the primary more so than the secondary – are responding to the same. Crucially, Network Neutrality creates a level of exemption for the Internet from the Schumpeterian cycle – but it does not immunise it. Innovation does not stop in its entirety, because even if the ‘necessity’ sourced from ‘monopolisation’ decreases, as is the case with a Net Neutrality enabled Internet, the necessity from other sources such as technological efficiency, penetration, cost-effectiveness, et alia, still prevails. That is why the models of internet themselves have advanced from dial-up to broadband to optical fibre (with drone- and hot air balloon-based provision of internet services being the latest in this regard), and the primary market has still seen continued evolution and innovation. Therefore, Network Neutrality puts the Internet somewhat outside the ambit of the monopolisation and destruction imagined by Schumpeter, but it does not mean that the Schumpeterian cycle shuts down.

But are we expecting too much of the Internet itself, and relying on it too much because of this? The internet as it currently exists is extremely different from what it was when it was created, and what was expected of it. The ‘internet’ as we know it is centralised, regulated, and subject to multiple levels and degrees of surveillance, something which is practically antithetical to its original image. And arguably, it is already well on the way to ‘monopolisation’ in many ways in its shifts towards the ‘neo-internet’, if not in the specific capitalist sense that Schumpeter spoke of, but with regards to the drawbacks that would come to the consumers from such monopolisation – i.e., increasing costs, increasing surveillance, increasing central regulation, so on and so forth. It is this very phenomenon that creates a need for newer services that run on the model of the original Internet, with the government arguably actually stepping into the shoes of the ‘monopolist’ to a certain extent.