[This post has been authored by Jalaj Jain of the Gujarat National Law University (GNLU), Gandhinagar.]

In the past decade, ‘consumer personal data’ has transformed from a mere tool of service to a ‘social currency’. Creation of regulatory barriers to determine the legal right of ownership and storage of data impacts consumer behaviour, stock markets and national elections. Indian authorities are struggling to introduce robust regulations, as they have failed to settle the debate regarding advantages and disadvantages of ‘cross border data flows’. On June 29th, 2020, Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology stated that under section 69A of the Information Technology Act, it had imposed a ban on 59 Chinese applications. Data security and privacy of millions of Indian citizens were cited as the main reasons for the questionable ban; contributing to the rising tensions between India and China. While such ban has both economic and security implications, the larger concern is to determine India’s stance on cross border data flows.

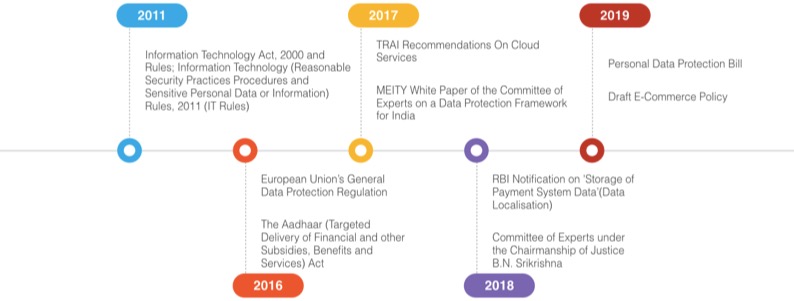

From a regulatory standpoint, the concept ‘cross border data flows’ remains subject to legal scrutiny due to archaic and vague governing framework. In this context, cross border data flows refer to movement of data across servers situated in different sovereign states. India’s conquest towards regulation of cross border data flows began in 2011 (refer to ‘Figure 1.1’). However, as early as 2006, China had introduced measures for e-banking that require such companies to keep their servers in China. Developing countries as compared to developed countries have a completely different approach towards cross border data flow regulation. Cross border data flows is a major trade law issue; both USA and Japan have signed a digital trade agreement, wherein they have renewed their stand against data localization and doubled down on the message of free flow of data through internet services.

Existing regulatory framework in the form of Sensitive Personal Data Rules, 2011 is very liberal. Under rule 7 of the same, as long a reasonable care is taken by a body corporate with regard to personal data, it can freely process and store that data outside India. In 2018, Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in order to have unfettered supervisory access to transactional data stored with payment system providers, stated that all system providers shall ensure that all data relating to payment systems operated by them are stored in a system only in India. Interestingly, Personal Data Protection Bill, 2019 places no restriction on the processing and transfer of personal data outside India. However, under the proposed legislation ‘sensitive personal data’ can only be stored in India, and may be transferred outside India for processing only with explicit consent in limited conditions. India’s latest Draft National e-Commerce Policy proposes to create a balance by mandating data localization with certain exemptions. Indian regulatory authorities do not have a unified approach.

Additionally, the Indian government and the citizens are not the only stakeholders. Cutting off data flows or making such flows harder or more expensive puts multinational firms at a disadvantage. Hence, tech giants lobby for liberal regulations with respect to Cross Border Data Flows as they intend to strategically build servers in more economical countries. For instance, the Asia Internet Coalition, representing giants like Twitter and Google, commended the removal of data localization from the e-commerce policy draft of 2019 which was later added again.

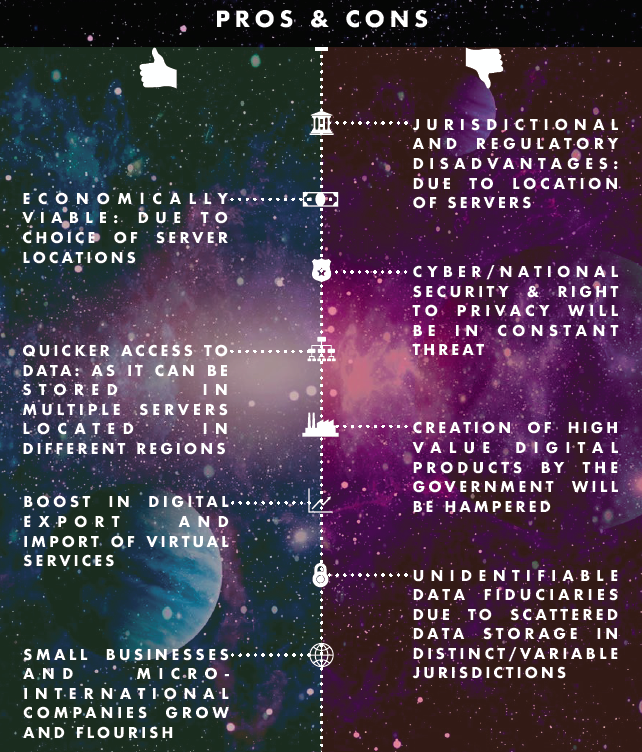

Analysis of Pros and Cons

It is prudent for the government to regulate data flow for two major reasons. Firstly, the authorities can protect the privacy of citizens and deal with cybersecurity threats quickly without foreign interference. Secondly, it can maintain a monopoly over the data of Indian citizens as the government can exercise its jurisdiction and make ad hoc decisions at any point of time without the interference of a private entity. Facebook’s failure to compel Cambridge Analytica to delete all traces of data from its servers located in the UK enabled the company to retain predictive models derived from millions of social media profiles throughout the 2016 US presidential elections. If there were stronger data localization laws, the US authorities could have directly dealt with the immoral use of such data. There are no set parameters to analyze a regulation without its limited implementation or an undeniable need.

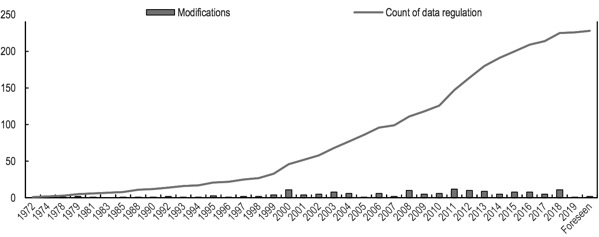

Cross-border data transfers have allowed consumers around the world to access a wider range of goods and services, at a lower cost. Cross-border data transfers have also enabled the creation of a new breed of MSMEs, the ‘micro-multinational’, which is ‘born global’ and is constantly connected. Traditionally, regulated industries generate returns in excess of their cost of capital, while relatively less regulated companies do not. However, businesses involving ‘Cross Border Data Flows’ are not capital intensive and internet companies operate differently from traditional businesses. Hence, over regulation (refer to ‘Figure 1.2’) can lead to a slower growth rate of digital industries. The biggest disadvantage of free flow of data across borders is that a cybersecurity threat can escalate and become a national security threat. The lack of jurisdiction of the Indian courts and Indian government over servers situated in a different sovereign state can lead to unidentifiable data fiduciaries as the location of the server will determine the influence of various state and non-state actors.

Concluding Views

As the supply of a commodity increases, it becomes less valuable due to the decrease in demand. The concept of ‘data’ defies the basic principles of economics when it is analyzed as a ‘commodity’, which can be stored and traded. As the supply of data increases, it becomes more valuable. Hence, the traditional parameters to regulate data cannot be used. For India, the most effective regulatory approach requires an ex-ante adequacy decision ensuring that countries meet specific conditions before data can be safely transferred. Where an adequacy determination has not yet been made, firms can move data under options like binding corporate rules, contractual clauses and consent. There is a pattern of migration from managed data servers to leased cloud services, and migration from cloud services located on foreign soil to cloud services in India. The primary reason that, unlike developing nations, USA and Japan have liberal regulations is that they have the ability to exercise influence/jurisdiction over big tech irrespective of where the servers are situated; due to the location of incorporation. From a trade law perspective, such developed nations have an unfair advantage over developing nations.

The distinction between ‘sensitive personal data’ and ‘personal data’ is the solution for sustainable regulation of ‘Cross Border Data Flows’. Personal Data is “any information relating to an identified or identifiable individual”. In India, sensitive personal data is given a wide interpretation due to the 2011 Rules. The ideal regulation is robust data localization with carefully curated exemptions. Unfortunately, the Srikrishna Committee has not proposed the concept of Regulatory Sandboxes, which provide a controlled environment to test such regulations. RBI and SEBI are trying to promote such sandboxes. Randomised controlled groups can also be formed based on regions to assess the impact of robust regulations as compared to minimal regulations, over a period of a few years. Based on the results, exemptions to data localization may be decided.

While the laissez faire strategy can boost internet-based industries and digital economies, they are also an ineffective tool to deal with foreseeable security threats. Hence, robust regulation with adequate exemptions is the method for sustainable penetration of technology in India. While the recent ban on Chinese mobile applications might be a political move, India needs a uniform regulatory approach with respect to cross border data flows.