(ImageSource: https://flic.kr/p/5kN3ek)

(This post was earlier published on SpicyIP)

ICANN and a Changing Internet

Ever since Swaraj covered the new domain names being permitted by ICANN back in 2011 on SpicyIP, there have been a few quite crucial developments. Before moving on to these developments, a quick background of some relevant points.

Part I: Introduction – background

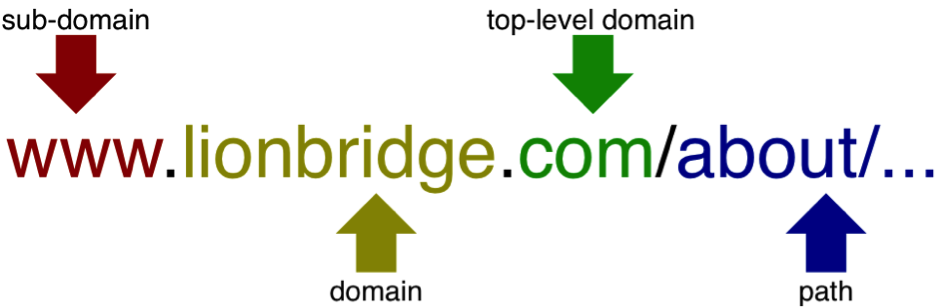

The Domain Name System is the current back bone of accessing the internet. It essentially acts as an address book of the Internet for computers, translating human-readable website addresses such as ‘spicyip.com’ to their unique numerical IP addresses that the browser can read, thereby allowing it to access the requested content. The human readable part of a domain name is divided into two parts – the name of the website, and the ‘TLD’ that comes after it. For instance, in ‘wordpress.com’, ‘wordpress’ is the name of the website, and ‘.com’ is the ‘TLD’. A very handy guide to the Domain Name System is available here, courtesy of the Internet Society.

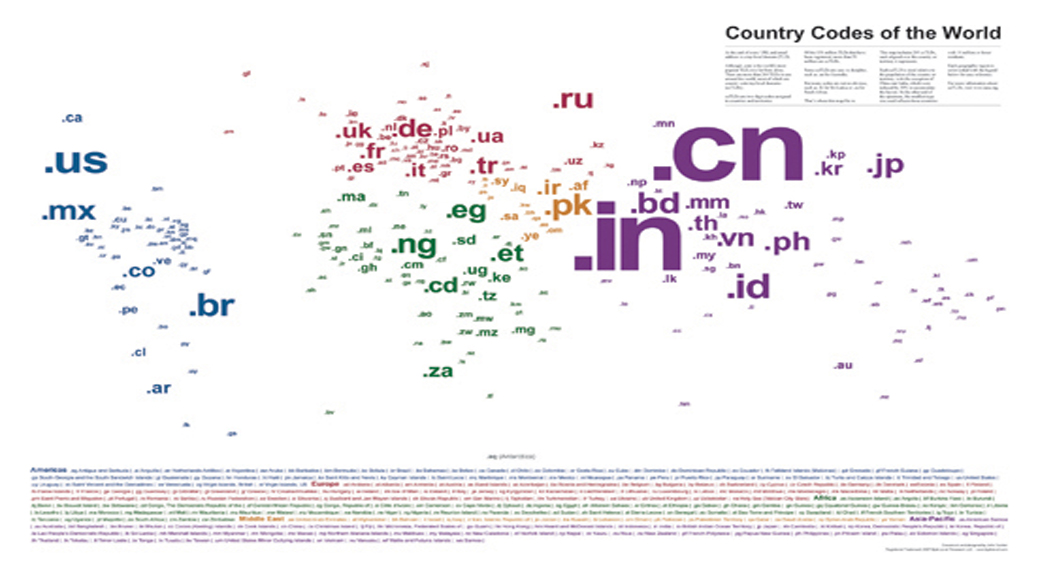

The term ‘TLD’ here refers to Top Level Domain. Each TLD is maintained by a separate Registry organisation, which has access to all the domain names ending in that TLD as well as the IP addresses associated with them. This is not to be confused with a ‘Domain Name Registry’, which is a database of all the domain names and associated registrant information regarding the TLD, and is maintained by the Registry Operator. These registries can further sell domain names in bulks to ‘Registrars’ rather than carrying out that function themselves, and these Registrars are free to charge whatever they wish for each domain name they sell, but they have to pay a fixed amount per domain to the registry. There are various types of TLDs, such as Generic Top Level Domain Names (gTLDs), Country Code Top Level Domain Names (ccTLDs, like ‘.in’ for India), Internationalized Domain Names (.在线, for China), so on so forth.

ICANN is in-charge of maintaining this ‘address book of the Internet’, the ‘root zone’. (You can view a handy chart of the root zone demystified here). Crucially, however, ICANN only manages the assignment of domain names. The actual technical implementation of any changes made to the DNS system is managed as a cooperative agreement between the American National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) and Verisign. Hence, the actual technical changes are to be made by Verisign – the relevance of this will be clearer later.

Until a few years ago, ICANN restricted the ‘gTLDs’ a number of now-popular names such as ‘.com’, ‘.net’, so on, which over time became synonymous with the Internet. In order to expand the Internet’s address book and allow for a more flexible Internet, the ICANN decided in 2008that it would expand this list, allowing registrations of any and all gTLDs. This plan was finally put into effect in 2012 after and amid long controversies. ICANN only allowed for a restricted form of expansion to begin with, restricting the number of applications it would accept to a thousand per year.

Part II: IP Concerns

There have been a number of concerns that have been raised with respect to the new gTLD system. Chief among these have been the problems they raise for trademarks and other forms of Intellectual Property, and the security of the Internet. Though there have been some concerns about the ICANN’s governance model, those are not directly related to this issue, and hence have not been covered here. This post focuses on Trademark and Security related issues, the former of which have been detailed below:

- The first major issue, and perhaps the most important issue from the IP perspective, is that of cybersquatting. The term ‘Cybersquatting’ refers to the practice of registering domain names using the trademark, brand, or other such content which belong to someone other than the person who owns the domain name. Cybersquatters then try to sell this domain name to the owner of the trademark or brand for a substantial profit. This can also lead to organisations registering domains ‘defensively’, in order to protect their trademark from cybersquatting, especially to protect it from being associated it what they would think is ‘harmful content’. Similar trends were observed when ICANN made the ‘.xxx’ domain available back in 2011, with organisations rushing to register their domains to make sure the adult content specific domains were not associated with their trademarks. The fear of and reaction to this phenomenon has been quite strong since the ICANN confirmed the new gTLDs.

- Drawing from the above is the issue of the costs involved in such defensive practices, which are expected to rise manifold as the amount of domains to be registered rises along with increasing gTLDs. Along with this, the amount of costs and manpower that would have to go into policing these domains is also expected to increase the necessary expenditure for the trademark owners by quite a lot.

- Another major problem that arises here is when there is an application or a dispute regarding a broad domain name, is that a multitude of people or different organisations can claim rights over. The best example of this is Reliance filing a claim for the ‘.indians’ domain,(update: which Reliance has since withdrawn) which would mean that any person or organisation planning on setting up a website with the ‘.indians’ domain would have to apply to Reliance for it. Other examples would be claims for domain names like ‘.restaurants’, et alia.

- The second major issue regarding the above topic, which draws largely from the third one to the extent of being overlapping, concerns the applications and disputes regarding even broader domain names that are arguably so broad that ideally no one organisation should own them. The quintessential example here is Amazon filing for the ‘.book’ domain name – an application that has been rejected.

Part III – Security and Architectural Concerns

The last three issues that are considered in this post involve the possible effects the new gTLDs might have on the security of the Internet, its architecture, and of users of the Internet.

- The first issue is that of ‘Name Collision’. The term ‘Name Collision’ is used to refer to a rather technical problem. Name Collision, as ICANN defines it, is when an attempt to resolve a name used in a private space results in a query to the public DNS – i.e., when two resolving terms are identical, yet serve different purposes. This phenomenon is somewhat similar to the ‘puns’ we observe in daily language. To draw a broad analogy, Name Collision is when you ask, as a Windows Mobile user, for ‘Cortana’, hoping to get Microsoft’s mobile assistant application, but ending up getting to the video game Halo series character. As ICANN mentions, this is not an issue unique to the new gTLDs, only one that becomes more prominent and risky with the new system. Keeping this in mind, ICANN has denied all applications for ‘.home’ and ‘.corp’ since they are already used very widely in home and company router systems. This should not, therefore, be a major issue in the coming times, and seems to be well in hand.

- Mentioned earlier in this post was Verisign, the American company contracted to manage the technical part of ICANN’s role. Early in the year 2013, it published a report titled “New gTLDSecurity and Stability Considerations”, which delves into the details of the issues faced by the program, and essentially asking ICANN to make sure it takes enough time to address each of them before going ahead with the new gTLDs to ensure a safe and stable Internet.

- Last and not the least, but perhaps one of the most obvious, is the heightened risk of Phishing(i.e., attempts at acquiring sensitive information through online fraud) with the new gTLDs, which will allow for even more believable emails from Nigerian princes, State Banks and Harry Potter websites, making it a bit more difficult to root such scams out.

Part IV – Redressal Mechanisms

To deal with some of the issues mentioned above, ICANN has rolled out certain new measures in order to bolster its security and dispute management processes. These include its Pre-Delegation Testing system, a Trademark Clearing House (TMCH), and an Emergency Back End Registry Operator (EBERO), Escrow requirements, Zone File Access, and Service Level Agreement Monitoring – all of which have been commented on in the Verisign report.

The Pre-Delegation Testing system is meant to ensure that the applicant in question is capable of maintaining a new gTLD in a secure and stable manner; the Trademark Clearing House works by maintaining a list of verified trademarks and related terms which are provided to registries and registrars, to prevent trademark infringement; and finally, the EBEROs are essentially backup TLD registries, that have been set up to take over in case a registry operator seems to be at the risk of failing to sustain the five critical registry functions enumerated by ICANN (DNS resolution for registered domain names; Operation of Shared Registration System; Operation of Whois service; Registry data escrow deposits; Maintenance of a properly signed zone in accordance with DNSSEC requirements).

While the current status of the systems cannot be commented on here, they were quite behind schedule at the time the Verisign report was published. To quote the report, “ICANN’s original plan was to select EBERO providers in June 2012 with simulations and drills in January and February 2013 and providers prepared to be live in March. While ICANN issued a [request for information] in July 2012 and developed a short list in December 2012, there are currently no signed/tested EBERO providers, to our knowledge.” It must be noted here that this report is admittedly a bit old, and the system seems to be rolling out comparatively smoothly. ICANN is also currently undergoing an important change, from a body under the umbrella of the United States Government to an independent international not-for-profit organisation (a very good explanation of the intricacies of this transition is available here). As of the time of writing this post, the Deloitte Trademark Clearing House is now online, along with a list of agents that are working with ICANN in this regard; ICANN has listed on its website two EBERO contractors, along with a potential third. Moving forward, there will inevitably be changes to the way trademarks work in the cyberspace because of the new domains, and many new interesting questions like the ownership of the name ‘.indians’. For now, it looks like ICANN’s systems are slowly coming online, the new gTLDs are set to be online in due course, with their new vision of the Internet, are here to stay.