[This post is authored by Shikhar Aggarwal, a third year student at National Law University, Delhi.]

This article covers the need for, and rationale behind, the concept of principled Artificial Intelligence (“AI”). It explores the broad contours of the ethical principle of AI responsibility and accountability, analysing how it may be adopted in India. While tort law and product liability may hold the human element behind AI liable for harms caused, the existing frameworks are insufficient for redressing harms caused by autonomous technologies.

What is Principled AI?

AI programs, seeking to simulate human intelligence, have made significant advances since the advent of the digital age. Empowered by Machine Learning techniques, these programs are generating massive amounts of data on a daily basis, with the need for regular AI programming and a human interface steadily decreasing.

That said, there are certain ethical and privacy-related concerns that have arisen with the increasing use of AI in our everyday lives: programmers and developers often assume that the existing data is neutral and free from bias. However, it has been observed that feeding in such biased data means that AI technologies often inadvertently end up perpetuating and reinforcing such biases. Further, with immense potential for making autonomous decisions, AI often raises the philosophical and legal question of its personhood and agency.

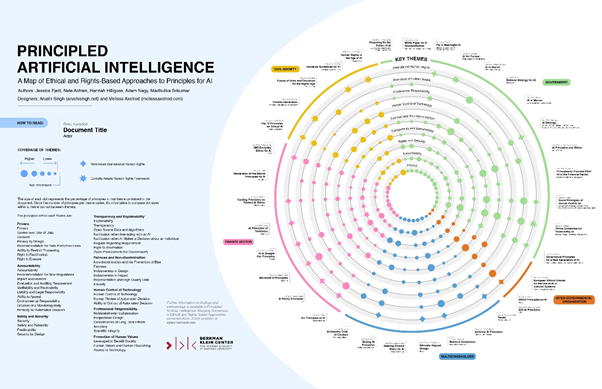

In light of these concerns, corporations, civil society organisations and governments have attempted to prepare policy-statements and guidelines for “ethical, rights-respecting, and socially beneficial AI”. Terming it as ‘Principled AI’, the Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society, Harvard University devised a circular map of ethical and rights-based approaches to principles for AI, identifying a common set of themes lying underneath them.

Inter alia, the Center referred to a Discussion Paper published by the NITI Aayog, on the National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence in June 2018. This Paper identified the key challenges to the adoption of AI in India, addressing its ethical implications. It also touched upon the accountability debate on AI, and recommended a negligence test for damages caused, and the formulation of safe harbours in order to insulate/limit liability.

Standards for AI Responsibility and Accountability

The principle of accountability emphasises the importance of human and expert oversight in preventing harms and addressing other ethical concerns. However, it also entails analysing whether the machines themselves can be held responsible for the harms caused. This, resultantly, raises further issues regarding the personhood of AI and questions on the attribution of intention and/or other ‘mental’ elements.

The principle of ‘responsibility’ is relevant throughout the lifecycle of an AI project: first, during the design-stage, impact assessments may highlight the potential harms of using AI in a particular situation; second, during the monitoring-stage, developers may undertake evaluations to ensure that auditing requirements are met; and third, during the redress-stage, liability may be ascertained where AI causes harm.

These principles are intrinsically linked with other themes and principles identified in the Harvard study. For instance, explainability of AI actions (the extent to which the feature values of an AI event are related to its model prediction, in a manner which humans can understand) is crucial for ascertaining responsibility. Since AI systems differentiate and process inputs through various forms of computation, developers may determine the inputs which have the greatest impact on the outcomes reached. Similarly, the property of ‘counterfactual faithfulness’ may enable developers to consider the factors which caused a difference in outcomes: it answers whether a particular factor determined the result, and what factor caused a difference in outcomes. Ultimately, this process of reason-giving is intrinsic to juridical determinations of liability.

Claims pertaining to the use of analogous automated technology may be useful in the development of jurisprudence on AI technology. For instance, in re Ashley Madison Customer Data Security Breach Litigation, the District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri held that the use of an automated computer program simulating human interaction on a dating website, in order to induce users to make purchases, could give rise to liability for fraud.

Furthermore, there have been cases involving personal injury resulting from automated machines, including those concerned with the safety of surgical robots. In Nelson v American Airlines, Inc., applying res ipsa loquitur, the Court found an inference of negligence by American Airlines, relating to injuries caused by a plane on autopilot. Such inference could be rebutted, only upon proving that the accident was not caused by autopilot, or was triggered by an inevitable cause. Therefore, it is clear that existing frameworks may be of some help in establishing accountability.

Scope for Application of Tort Law and Product Liability to AI in India

The most commonly-invoked tort of negligence requires establishing breach of a duty of care, which causes harm to the plaintiff(s). Tort law also requires proving factual and legal elements of causation, which may be taken care of by improved explainability of AI actions.

In accordance with the Rylands v Fletcher rule of strict liability, manufacturers, owners or users may be held strictly liable for acts/omissions of AI if the technology in question was characterised as a dangerous object (say, a lethal autonomous weapons system), or fell within the scope of product liability. This involves holding human developers liable for all consequences, whether foreseeable or not, arising from any ‘inherently dangerous’ technology.

In India, the newly-enacted Consumer Protection Act takes a similar view. It defines product liability as “the responsibility of a product manufacturer or product seller, of any product or service, to compensate for any harm caused to a consumer by such defective product manufactured or sold or by deficiency in services relating thereto”. Additionally, Chapter VI of the Act governs the product liabilities of manufacturers, service providers, and sellers separately, along with prescribing a limited set of exceptions.

The Act also expands the definition of unfair trade practice, to include disclosures of personal information given in confidence by the consumer to any other person(s). The ambit of such a safeguard may be redefined in a manner which provides consumers with an opportunity to get redress for the detrimental effects of data driven decision-making through AI technologies.

The root of these formulations can be traced back to United States v Athlone Indus., Inc., where the Court held that robots cannot be sued, and discussed how civil liability may be imputed upon the manufacturer of a defective robotic pitching machine, for its defects.

These traditional rules of liability may not suffice in case of AI technologies capable of making autonomous decisions. In these cases, it would not be possible to identify the party responsible for causing harm, and/or to require the said party to compensate for the same.

Additionally, there are problems with invoking product liability for AI. When product liability claims are directed towards software failures, it should be noted that programming codes installed into a system are generally considered as ‘services’ than ‘products’. Such claims have proceeded as breach of warranty cases, without involving product liability.

Therefore, it is extremely difficult to draw a line between damages resulting from self-decision capabilities of AI technologies, and damages resulting from product-related defects, unless such independent decision-making is itself seen as a defect. However, holding a human manufacturer/programmer liable for independent decisions of AI technologies would be excessive and may ultimately disincentivise innovation.

What can be Done? What remains to be Done?

The problems concerning autonomous systems have led to calls for conferring legal personhood upon them. This question impinges upon and runs parallel to the question of ascertaining AI liability. Given that personality may be separated from humanity (as is done in the case of corporations), several practical and financial reasons may become important factors in granting some form of artificial personhood to AI systems, notwithstanding the normative jurisprudence behind this discourse.

It has even been suggested that a principled approach towards AI in itself may have limited impact on designing and governance. This is because several ethics initiatives have largely produced unclear and high-level principles. These value statements, which seek to guide actions, are unable to provide specific recommendations in reality; they have not addressed core normative and political strains in critical discussions on fairness, privacy, and responsibility/accountability associated with AI.

AI in India needs to meet certain ‘ethical strongholds’. These strongholds would not only prevent the development of complex adaptive AI systems leading to self-sustaining and malicious evolution, but also improve the quality of decisions taken and work done by human beings. To that end, strong emphasis must be laid on cyber-resilience, data privacy, accountability and mitigation of high-risk failures, through comprehensive guidelines on ethical issues, developed in consultation with local stakeholders.

In India, there are other structural issues which impede the development and use of AI to its full potential: first, unclear privacy, security and ethical regulations, second, inadequate availability of expertise, workforce and skilling opportunities, third, high costs and low awareness on benefits of adoption of AI in business processes. Hence, ethical AI is an opportunity which can be best tapped in India only in the coming future.

Conclusion

In spite of concerns, it is sufficiently clear that an umbrella prohibition on evaluative decisions taken by automated decision-making processes would limit the benefits of AI technology for a country like India. Development of concrete tools and practices, including feedback loops between human and AI decision-making, would not only reduce discriminatory and unethical outcomes, but also enable India to reap the benefits of AI. However, the principled approach, in itself, may be insufficient to address the tensions arising from the inadequacy of legal frameworks governing autonomous technologies.

Recommended Readings

- Anna Jobin, Marcello Ienca, and Effy Vayena, ‘The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines’ [2019] Nature Machine Intelligence 389.

- Brent Mittelstadt, ‘Principles alone cannot guarantee ethical AI’ [2019] Nature Machine Intelligence 501.

- Frank A. Pasquale ‘Toward a Fourth Law of Robotics: Preserving Attribution, Responsibility, and Explainability in an Algorithmic Society’ [2017] 78 Ohio State Law Journal 7.

- Julia Pomares and Maria Belén Abdala, ‘The future of AI governance’ [2020] Global Solutions Journal 84.

- Thilo Hagendorff, ‘The Ethics of AI Ethics: An Evaluation of Guidelines’ [2020] 30 Minds and Machines 99.