This post has been authored by Aryan Babele, a final year student at Rajiv Gandhi National University of Law (RGNUL), Punjab and a Research Assistant at Medianama. On 23rd October 2019, the Delhi HC delivered a judgment authorizing Indian courts to issue “global take down” orders to Internet intermediary platforms like Facebook, Google and Twitter…

Tag: Freedom of Speech

Article 13 of the EU Copyright Directive: A license to gag freedom of expression globally?

The following post has been authored by Bhavik Shukla, a fifth year student at National Law Institute University (NLIU) Bhopal. He is deeply interested in Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) law and Technology law. In this post, he examines the potential chilling effect of the EU Copyright Directive. Freedom of speech and expression is the bellwether…

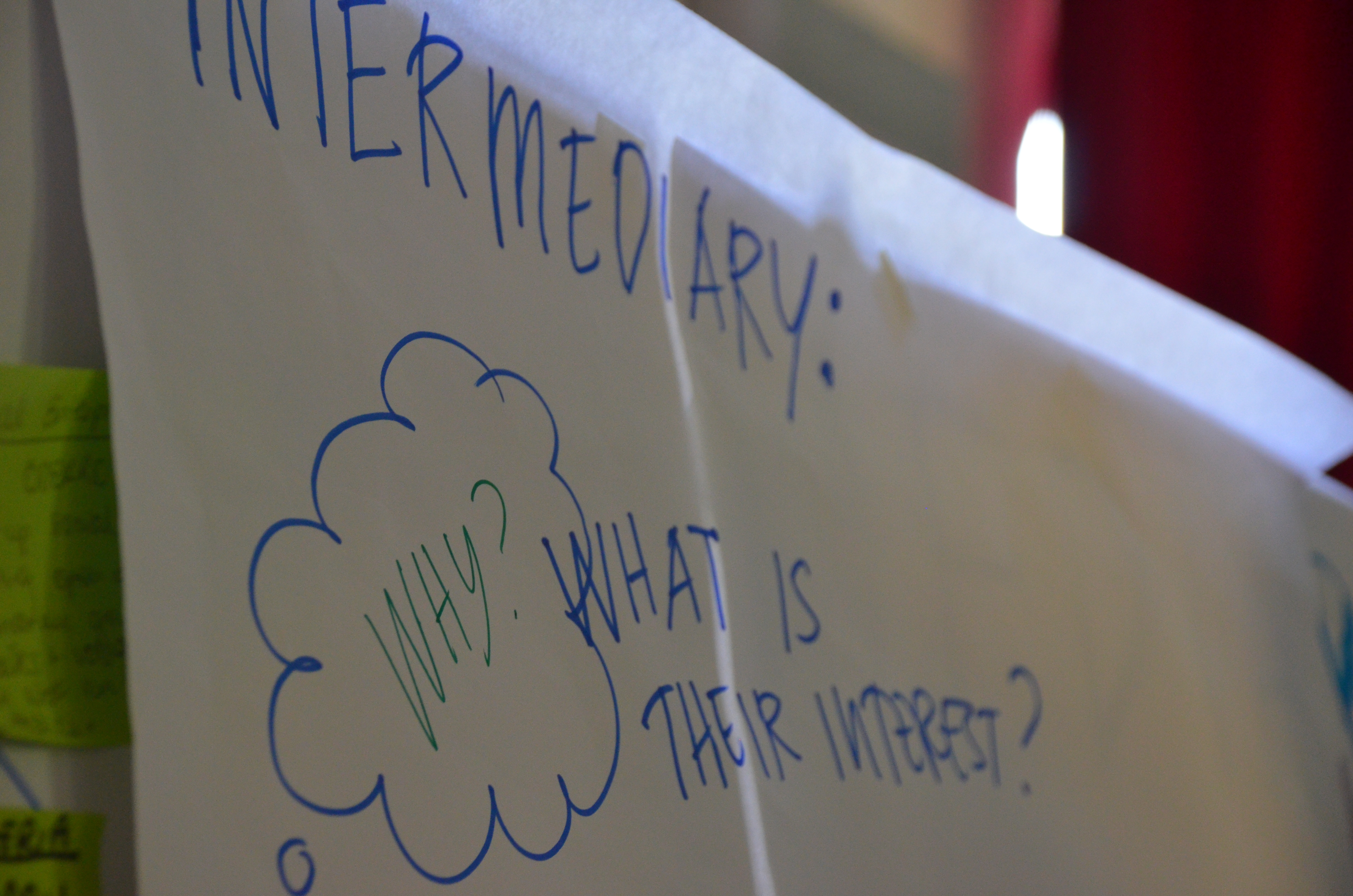

Intermediary Liability – An Explanation

(Image Source: https://flic.kr/p/o9EcaJ) Definitions and Explanations – the Concept of ‘Incentives’ An intermediary is an internet-based service provider, which provides its users with a platform to upload all and any types of content, ranging from text to videos. Some of the more popular examples of intermediaries would be Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, WordPress and Blogspot. The…

On Kill Switches, Media Silence, and Governmental Super-Powers – A Comment on Vadodara

(Image Source: https://flic.kr/p/5V1h4R) The following is a post on the recent disconnection of mobile internet, bulk SMS and bulk MMS services by the government in Vadodara in light of social unrest and riots. It’s a bit of a long post, and therefore has been divided into sections – the first part details the factual background of…