This piece has been authored by Lokesh Vyas, a fourth year law student at Institute of Law, Nirma University, Ahmedabad. Here, he gives a lucid explanation of issues posed by the increasing use of algorithms.

The Cloak of Algorithms

Unlike the traditional market, the digital economy does not have any geographical limits. Thus, there is fierce competition among all the players. However, due to the unequal availability of resources, it is becoming increasingly difficult for new aspirants to join the market. The use of pricing algorithms, presently adversely affects the present landscape of online retail.

An algorithm is an established computational procedure that takes a set of values, as input and produces another set of values as output. A catena of algorithms is used in the market to create artificial transparency.[1] These algorithms are called pricing algorithms because competitors in the market use them to set prices after gauging market behavior and competitors. They help competitors to outlive others through optimum pricing. Such a scenario creates artificial algorithmic transparency in the market. However, with an increase in such algorithms in the market, it becomes easy to predict the change in the market. An increase in the accuracy of such predictions, not only strengthens the dominance of certain competitors but also eliminates small competitors altogether, hindering consumer welfare.

Unilateral decision making, the right to make intelligent decisions is a fundamental right of any business, since they aim at maximizing profit. The exercise of such a right effectuates conscious parallelism which is a legitimate and obvious factor in any market. However, the artificial transparency that continues to exist due to algorithms enables competitors to control the market.

Further, the increasing transparency in the market creates interdependency among the competitors, thereby incentivizing collusion. Algorithms create a god’s eye view, enabling competitors to monitor activities in the market in real time. Market players are less likely to deviate because of the instantaneous fear of retaliation.

Hence, the algorithms become a cloak to escape liabilities under competition law. Such tacit collusion has not been considered not barred by the law.

Challenges

The primary question is, does traditional competition law accommodate the recent trends in the market such as pricing algorithms and if so, how? The challenge before competition law authorities is to detect whether tacit collusion exists among competitors, and whether it negatively impacts consumer welfare.

Additionally, questions about communication and liability arise. The absence of explicit communication is a major issue when considering collusion, because in order to prove collusion, there must be an existence of communication. Algorithms have enabled companies to escape the necessity of explicit communication.

Another issue associated with such algorithms is that of liability, because there is no human intervention which facilitates such tacit collusion. Thus, it becomes difficult for authorities to ascertain the liability of the final wrongdoer. The three possible assertions with respect to liability are; the liability of the person who invents such algorithms; the liability of the person who deploys them; the liability of the person who gains from such algorithms.[2]

None of the above acts are explicitly prohibited by law unless a mala fide intention [intentional cartelization] to cause harm is proved. Competition law only outlaws bilateral or multilateral decision making by the competitors because it implies the existence of cartelization. By contrast, the adoption of pricing algorithms through undertakings merely enables them to attain dynamic pricing. The issue arises when competitors maximize their profit by colluding with each other, by entering into automatized virtual agreements. As per the current debate on algorithmic collusion, algorithms are used to facilitate an existing price agreement between the competitors. They simply act as intermediaries, as an extension of the human will. Alternatively, the algorithms are designed to result in a tacitly collusive result. Here, unilaterally designed algorithms learn to tacitly understand each other due to limited market characteristics. Presently, two scenarios emerge when considering algorithms that could cause collusion.

The first is the ‘messenger scenario’, since here algorithms acts as an instrument of collusion, including the implementation of agreed price adjustments as well as the monitoring of such agreements. An example of this is the US Department of Justice and UK Competition and Markets Authority’s proceedings regarding the distribution of posters through the Amazon Marketplace. Here, the companies involved initially agreed via e-mail that they would not underbid each other. After an attempt at the manual adjustment of prices had proved too complex, both companies used (different) repricing software. Pertinently, this software made it possible to monitor competitors’ prices and dynamically adjust one’s own prices according to those of competitors. The software was set so that the products were offered at the same price as long as no third (uninvolved) dealer with a lower price was active on the market.

In the second scenario, a collusive market comes about because the behavior of companies is canonically harmonized by using similar algorithms or by using algorithms which adapt to change in the others. Such agreements do not come under the general definition agreement, however there exists a tacit ‘meeting of mind’ among the competitors. Hence, the traditional definition of a contract under competition law needs to revisited in order to include such collusion. Notably, the definitions of an anti-competitive agreement under Section 3 of the Competition Act, 2002, Section 1 of the Sherman Antitrust Act, 1890, and Article 101 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union do not cover mere ‘meeting of mind’ which exists due to such virtual agreements.

The use of algorithms in the market cannot be curbed altogether, since it would tremble the pillar of the digital economy. However, there is a need for regulatory policies to accommodate for the status quo. Pertinently, mutual price monitoring—the crux of tacit collusion which is not prohibited by Competition Law—must be addressed again.

The meaning of communication, a pre-requisite for constituting anti-competitive behavior also needs to be revisited to prevent ‘algorithm driven cartelization’. Pricing algorithms create a barrier for new entrants which in the long run affects market efficiency. Such a barrier is likely to impede the innovation in the market, which has direct nexus with consumer welfare.

Information Technology Act, 2000

There have been a lot of cases where e-commerce platforms and social media websites have been cleped as intermediaries, however, it is largely connected with the content uploading. Similarly, Section 2 of the recent Motor Vehicles (Amendment) Act, 2019 defined aggregators such as Uber and Ola as digital intermediaries or marketplaces which can be used by passengers to connect with cabs. The question of intermediary liability primarily deals with content uploading or verification, and attracts the applicability of IP laws or other criminal laws.

However, the competition in the market is so fierce today, that independent firms like Feedvisor and Intelligence Node have started offering algorithmic pricing as a service. Here, the question arises whether such firms are intermediaries under section 2(w) of Information Technology Act, 2000 and do not attract liability (see Section 79 of the Act) because they are a link that collects the information of various competitors and compares them to produce the best results for a third party. Thus, the applicability of the safe harbor provision on algorithm deploying companies also needs to be considered, since they are aware about the effects and utilization of these algorithms.

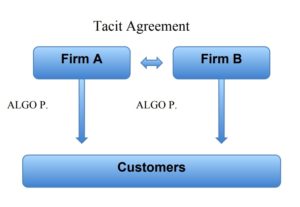

- Algo 1- Algorithm P

- Algo 2- Algorithm P

[The above diagram demonstrates a scenario where a common algorithm (Algo P) is used by two different business entities(Firm A & Firm B).]

Conclusion and Suggestions

There have been four approaches to solving the above problems so far:-

- To broaden the interpretation of competition laws;

- To insert new provisions in the existing legislation;

- To use more rigorous alternative methods of dispute resolution; and

- To act in a way that parallel consciousness would not happen.

The underlying assumption of all the above approaches is that algorithms are inherently perilous to the market and pose threats to the fair competition in markets. The heart of the entire pricing algorithms debate revolves around the term ‘contract’ which needs to be revisited and interpreted. The term contract/agreement connotes ‘meeting of mind’ and the meeting of mind suggest the intention of the parties to agree on something. The most strenuous task before the competition law agencies is to ascertain such intention even when such explicit agreement is lacking.In order to curb the above challenges, the intervention can either be in the form of making big legal changes (e.g. Expanding the scope of major offenses like cartelization and abuse of dominant position) or to come up with small interventions (such putting a cap on the price change for more than a certain number of times in a day).

Therefore, competition law authorities can retaliate to such changes by bringing enforcement algorithms which can detect deviant or anomalous behavior in the market and thwart them timely.

[1] See Virtual Competition by Ariel Ezrachi and Maurice E. Stucke.

[2] See Virtual Competition by Ariel Ezrachi and Maurice E. Stucke.

Figure taken from here.